Overview

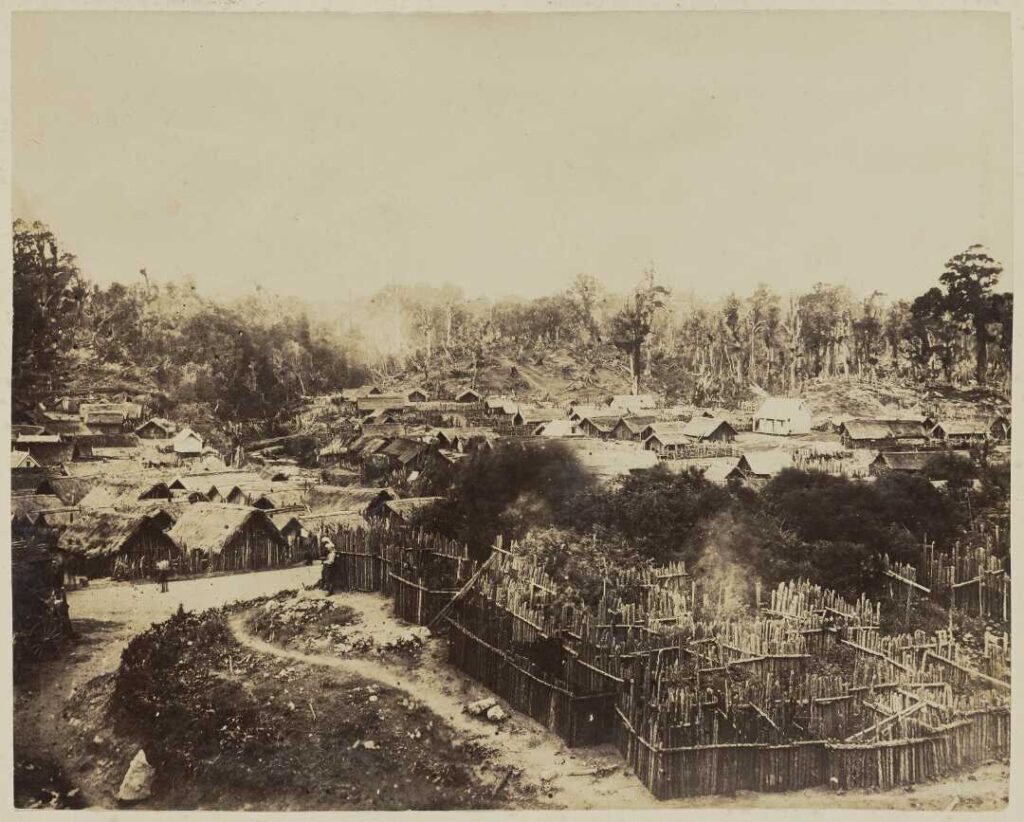

Photo Credit: Overlooking Parihaka Pa. Parihaka album 1. Ref: PA1-q-183-07. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23146877

For further info try our Library Archive (Ngā Taonga a Tamarau)

Before the wars of the 1860s had ended, in late 1865 or early 1866, a movement for peace and independence was established at Parihaka in western Taranaki under the leadership of Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kakahi. In the early 1870s, the settlement that Te Whiti and Tohu established under these principles grew rapidly as Maori displaced by confiscation and war arrived from throughout Taranaki. The permanent population of Parihaka consisted of Maori from throughout Taranaki and beyond, including Te Atiawa.

Throughout the 1870s, the Crown continued in its efforts to make the previously-confiscated Taranaki lands available for European settlement. In 1878, Parihaka and south Taranaki Māori leaders allowed the Crown to survey lands in south Taranaki on the basis that large reserves would be made for Maori occupation and that burial places, cultivations, and fishing grounds would be protected. However, after Maori became concerned that the surveyors were not marking out reserves that Crown officials had promised them, Te Whiti and Tohu ordered the surveyors to be peacefully evicted from the lands. In the following weeks, communication between Parihaka and the Crown broke down. Te Whiti, who by this time wielded significant influence among many Taranaki Maori, stated that the surveys should not be opposed.

At the end of May 1879, Te Whiti and Tohu directed men to plough settlers’ land throughout Taranaki. Premier Grey understood the action to be an attempt to draw his attention to land issues in Taranaki, and an assertion of a legal right over land that had been confiscated or alienated from Maori in other ways.

Many settlers felt threatened by the protests and demanded an increased armed presence, while others volunteered to serve in the event of a war. The Crown began to arm large numbers of settlers and place Armed Constabulary officers around the Taranaki district. However, the Crown also advised settlers, on several occasions, not to take the law into their own hands. In June 1879, Governor Grey instructed the head of Crown forces in Taranaki to arrest any ploughmen whose actions were likely to lead to a disturbance of the peace.

Between 30 June and 31 July, 182 ploughmen were arrested at locations around Taranaki, including Tikorangi, Bell block, and Huirangi in the Te Atiawa rohe. They were charged under the Malicious Injuries to Property Act 1867 with causing to damage to land exceeding £5 in value. Some were also charged with “conduct calculated to cause a breach of the peace”. The first 136 ploughmen arrested, including a number of Te Atiawa people, were sent to Wellington to await Supreme Court trial.

The final forty-six ploughmen arrested were tried in the New Plymouth Magistrate’s Court between 23 and 29 July 1879. They were found guilty of charges including causing damage to land “to the extent of over £5” and disturbing the peace. They were sentenced to two months’ imprisonment in Dunedin, and required to pay £600 sureties each for good behaviour for a period of twelve months. Those arrested at Bell block were ordered to serve their initial two-month sentences with hard labour.

Soon after the last of the ploughmen were arrested, Parliament passed the Maori Prisoners’ Trial Act 1879. The preamble of this Act stated that it was necessary for “the ordinary course of law [to] be suspended”, so that the Crown could alter the time and location of the prisoners’ trials if “for any reason, it is expedient”. The Act was extended in December by the Confiscated Lands Inquiry and Maori Prisoners’ Trials Act 1879. In January 1880, all of the prisoners being held without trial in Wellington were transferred to prisons in Dunedin and Hokitika.

In July 1880, the Maori Prisoners Act was passed to dispense with trials altogether, despite strong opposition from some Members of Parliament. Section 3 of the Act provided for the continuing detention of those prisoners who had not received a trial. Accordingly, all of the first 136 ploughmen arrested were deemed to be ‘”lawfully detained”, and continued to be held in South Island prisons without the benefits of a trial.

Section 3 of the Maori Prisoners Act 1880 also applied to those prisoners who had been tried and convicted, and whose twelve-month sentences for being in “default of entering into sureties to keep the peace” were due to expire the week after the Act was passed. The application of section 3 to these forty-six prisoners, most of whom were Te Atiawa, meant that all of them were detained for periods longer than the sentences imposed by the court. Crown proclamations extended the provisions of the Act for additional three-month periods on 26 October 1880, and again in January and April 1881.

In early 1880, the Crown sent forces to build a coastal road through the Parihaka district. When the road reached the Parihaka block, Crown forces pulled down fences around Maori cultivations, exposing them to their horses and wandering stock. Some soldiers also looted Maori property. As the fences were broken, Te Whiti and Tohu sent fencers to repair them. Crown forces began to arrest the fencers on 19 July 1880.

In August, Parliament passed the Maori Prisoners’ Detention Act 1880 to ensure that fencers arrested after 23 July 1880 could also be detained under the provisions of the Maori Prisoners Act 1880, the terms of which had only applied to those who were already in custody at the time it was passed.

None of the first 157 fencers arrested received a trial. All were sent to South Island prisons. No records of the tribal affiliations of the fencers arrested seem to have been made. However, these prisoners were very likely broadly representative of the Parihaka population at the time, known to include people from Te Atiawa.

On 1 September 1880, Parliament passed the West Coast Settlements (North Island) Act, which made some of the activities that had characterised the protests, such as removing survey pegs, erecting fences, and ploughing, criminal offences. On 4 September 1880, fifty-nine more fencers were arrested, tried under this Act, found guilty of obstructing a constabulary road, and sentenced to two years of hard labour in Lyttleton. The final seven fencers arrested on 5 September were sent directly to Lyttleton without trial.

In total, the Crown imprisoned 405 Maori, including 182 ploughmen and 223 fencers, for their participation in the peaceful resistance campaigns of 1879 and 1880.

Prisoners performed hard labour, and evidence suggests that some fell ill through a combination of harsh conditions and an unfamiliar climate.

Contemporary reports suggested that some of those Parihaka prisoners transferred to South Island jails experienced gross overcrowding, and that several were subject to solitary confinement with bread and water rations for “trifling offences”, some for up to two months. Some of those imprisoned later reported that they had been forced to swim out to sea and back at gunpoint. The last prisoners were released in June 1881. Taranaki Maori oral traditions record the grief that prisoners suffered as a result of their separation from their homes, community, wives, children and families.

Some Te Atiawa prisoners died while in exile from Taranaki. In 1880, Watene Tupuhi and Pererangi of Te Atiawa died of consumption in Dunedin, and in 1881, another Te Atiawa member, Pitiroi Paekawa, died of unknown causes. All three men were buried in paupers’ graves in Dunedin’s North Cemetery.

On several occasions, senior Crown figures stated that the duration of the prisoners’ detention was determined more by the political situation in Taranaki than by the particular offences with which they had been charged, and in some cases, convicted. In January 1880, the Governor issued a proclamation in which he stated that “acts of lawlessness have taken place which endanger the peace of the country, and prisoners are held in prison till the confusion is brought to an end.” In July 1880, the Native Minister spoke in support of the Maori Prisoners Act 1880 by stating that “it mattered very little whether [the prisoners] had been brought to trial or not. If convicted, they would not perhaps get more than 24 hours’ imprisonment for their technical offences. The trial meant nothing so far as the detention of the prisoners was concerned.”

Numerous contemporary newspaper reports described the arrested ploughmen and fencers as political prisoners. In August 1880, the Crown-appointed West Coast Commission concluded its final report by stating that Taranaki Maori were being imprisoned “not for crimes, but for a political offence in which there is no sign of criminal intent”.

On 7 October 1880, the Crown released twenty-five ploughmen as an “experiment” to gauge how Taranaki Maori, and the prisoners themselves, would react. The next release of prisoners did not occur until December 1880, approximately eighteen months after the first ploughmen were arrested.

In January 1881, John Bryce resigned as Native Minister after failing to convince his colleagues of the need to take “active measures” against Parihaka. He was replaced by William Rolleston, who favoured a more moderate approach. Under Rolleston, the rest of the prisoners were released, and all were returned to Taranaki by June 1881. Those fencers released at this time had been in prison for between 10 and 12 months, while those ploughmen released had been in prison for almost two years. A few of those released were reported to be very unwell.

The Invasion of Parihaka

In June 1881, Crown forces, engaged in road-making again opened fences surrounding cultivations near Parihaka. Residents of Parihaka, including Te Atiawa people, again repaired them. In August, Māori from Parihaka and surrounding settlements began to clear and fence traditional cultivation sites, some of which lay on coastal sections that the Government had already surveyed or sold to European settlers. As tensions escalated, the Crown again increased the Armed Constabulary presence around Parihaka to over 1,500 men.

On 5 November 1881, more than 1,500 Crown troops, led by the Native Minister, invaded Parihaka. No resistance was offered. Over the following days, some 1,600 men, women and children not originally from Parihaka were forcibly expelled from the settlement and made to return to their previous homes. Houses and cultivations in the vicinity were systematically destroyed, and stock was driven away or killed. Some looting also occurred during the occupation, although this was against orders and resulted in the dismissal of some members of the Crown’s forces. Special legislation was subsequently passed to restrict Maori gatherings, and entry into Parihaka was regulated by a pass system. Taranaki Maori, including Te Atiawa, assert that women were raped and otherwise molested by the soldiers.

Six people were arrested during the invasion, including Te Whiti and Tohu, who were charged with sedition. Their trials were postponed, and ultimately, special legislation was passed to provide for their imprisonment without trial. Te Whiti and Tohu were held until March 1883. A second piece of legislation was passed to indemnify those who, during the invasion of Parihaka, had carried out certain acts which “may have been in excess of legal powers”.

Some 5,000 acres of the promised reserve at Parihaka were taken by the Crown as compensation for the costs of its military activities at Parihaka.

The Sim Commission concluded in 1927 that the Crown was directly responsible for the destruction of houses and crops, and “morally if not legally” responsible for the acts of the soldiers who were brought into Parihaka. It recommended the payment of £300 as an acknowledgement of the wrong that was done to the people of Parihaka.

Scenes of Parihaka

Photo Credit: The following images are from the Alexander Turnbull Library Collection: Overlooking Parihaka Pa. Parihaka album 1. Ref: PA1-q-183-07. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/2314687

Click images to enlarge.